This blog was first published as a case study in the Creatively Minded and Refugees report by Counterpoints Arts which explores how the arts can support refugee mental health.

Write to Life is a long-running writing and performing group for survivors of torture from around the world who are or have been asylum-seeking clients of Freedom from Torture in Finsbury Park in London. I and my volunteer mentors run group workshops every two weeks, and each group member also is paired up with a writing mentor, with whom they have one-to-one sessions.

All the group members are current or former clients of Freedom from Torture. They come from many countries, but for some reason the majority are currently from sub-Saharan Africa. They are referred by their therapist or counsellor, sometimes with a pre-existing interest in creative writing, but more often for other reasons: because they feel a need to tell their story, they feel survivor guilt to be alive when others are not, or are in danger because of them, and want to bear witness – or just to improve their written and spoken English.

We talk and mostly write in English, but there’s some give and take with Francophone African clients to get the exact translation from French to English.

Our practice

We believe Write to Life is unique in the world: as a group for people whose existence has been almost obliterated by torture, not just physically reaching the brink of death but psychologically being made to feel they have no value. But also, because it’s been in continuous existence for nearly 25 years, in which time dozens of group members have come and gone, but one or two are still with us, still writing and still benefiting.

Our members have widely varying levels of English when they join, and come from a huge range of educational, cultural and social backgrounds, but they all share the horrors of a traumatic past. This gives them, over time, a powerful bond: often they can’t trust others from their own country, either because they may be government agents or because they’re from the ‘other side’ in a conflict there. So, they may be very lonely and isolated, and over time the group becomes like a second family. For this reason – and because some members travel huge distances to come to us, we start each session with a basic meal, which is also an opportunity to catch up.

The theme of the workshop varies: sometimes it supports a communications or fundraising objective of the organisation, but as these are closely aligned with members’ concerns, that works fine. Sometimes we write about common experiences: journeys, belonging. Sometimes we choose a more technical approach: metaphor, beginning and ending a story. And occasionally, it’s practical, anything from performance technique to how to write an ‘alternative CV’ or face an interview.

We ask everybody to write: this is important, so we all feel committed. But people don’t have to read their work out, if they feel it’s unfinished, or they find themselves having written something too personal. But people usually do want to share, to be heard, and the affirmation they get from each other is a powerful incentive to continue and finish their work after the workshop is over.

But the true and major benefit of what we do is often seen in the work produced in the one-to-one sessions. We never ask them to write about their trauma in the group, and when on occasion a group member writes, and shares, something that could potentially trigger others, we have been known to intervene and ask them to stop reading. But in the private sessions with their mentor, they can explore whatever feels most urgent; and very often, this turns out to be their own personal history.

Writing about it has many benefits: it takes the experience out of their head, where it destroys their calm and often their ability to sleep, and puts it outside, on a page, where they are in control and can retell and shape it. In doing so they learn about themselves and their own responses, and learn what they need to do to move forward. And seeing where the narrative is disordered, or has gaps, enables them to see what they may be suppressing, or fearing most. The more they write, and rewrite, the more distance they can put between themselves and the experience.

“Writing about [their experience] has many benefits: it takes the experience out of their head, where it destroys their calm and often their ability to sleep, and puts it outside, on a page, where they are in control and can retell and shape it. In doing so they learn about themselves and their own responses, and learn what they need to do to move forward.”

And, of course, there is the power of writing as art. The emotion, the raw experience they bring, is like the rocket fuel that powers their stories and keeps them writing. The beauty of the form and the words, whether as a poem or a prose narrative, sheaths the story, deflects the resistance of an audience to yet more bad news, and slips behind their defences by hooking them in and absorbing their attention.

One of the biggest challenges both for myself and for the volunteers who mentor our writers is that wider support from the organisation is time-limited. Often mentors develop a very close bond with their writers – which is good and perhaps necessary, for the writer to entrust their most private feelings and experiences to the mentor. But it can also lay a heavy burden on the mentor, who is not trained for this and whom we cannot materially support to help the writers.

We are lucky at the moment in that my Deputy Coordinator happens to work as an asylum support officer in her other job, so she has an expertise in signposting, but that’s incidental.

A key struggle for us is that Write to Life engages with members who are no longer able to access clinical treatment, legal and welfare support after three years. This loss of official support leaves us in a difficult position, supporting individuals with complex needs in spite of lack of qualifications, training, resources and support.

The other major challenge at the moment is the difficulty of recruiting and retaining mentors as volunteers. Fewer and fewer people in the arts, with the backgrounds we need, can afford to do this work for free.

It has helped me: by writing I released my soul, took out my pain that has been stored inside. By writing down, it’s like sharing this pain. I’ve been in Write to Life for two years, since 2019. Writing helps me to express myself and relieves the sorrow inside me. It’s helped me to write in a new language, as I was a French and Senoufo speaker before. But above all, it’s revealed a poetic gift that I didn’t know I had. I never liked to read or write before, I didn’t know about poetry, it has shown me what I can do if I push myself. I think everybody should join Write to Life!

Nalougo

Impact and change

As well as the bi-weekly workshops and one-to-one sessions, we produce occasional or Zines of our work, in which everybody participates, and also do more public single projects in which people can choose, or not, to participate. The publication is important to motivate members to write, and feel there’s a point to their writing, and an audience for it, beyond the group itself.

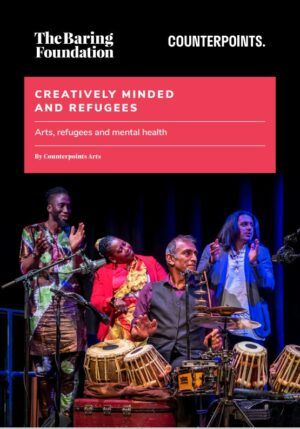

The extra projects are a step up into a different league of both writing and performance for participants. We began with appearances at literary festivals, but then progressed to developing and performing original works in partnership with a variety of arts organisations and venues, including the Roundhouse, Tate Britain, Southbank and the V&A. Most recently we’ve done two collaborations with a local arts and music charity, ‘NWLive’, culminating at sold out performances and standing ovations at Kings Place and the Bloomsbury Festival.

The benefit to Freedom from Torture is obvious: we take their work to audiences who’d never otherwise be interested and provide an uplifting and inspiring counterpoint to the campaigning work they do.

For the participants, the benefits can be even greater. Nothing beats that feeling of holding an audience’s rapt attention, unless it’s holding it with something you’ve written yourself, often in your fourth or fifth language. More than once I’ve been told that this experience, of performing, and seeing and hearing that attention in front of them, is like having a mirror held up: realising they still exist, despite every attempt to destroy them.

So, as a result of our work, Freedom from Torture has gained audiences and supporters, and our members have gained the confidence to go back into the world and start, and lead, successful new lives in a new country. Their trauma may never leave them, but they learn to live with it, and even see surviving it as something gained, something to remind them of their own strength.

Their trauma may never leave them, but they learn to live with it, and even see surviving it as something gained, something to remind them of their own strength.

At the moment, as mentioned above, we’re trying to rebuild the group after the pandemic by returning to in-person workshops and recruiting new mentors. We’re planning another collaboration with NWLive and Kings Place, and contemplating a new excursion into performance poetry, which we haven’t done before, and which will provide an opportunity to collaborate with Young OutSpoken Survivors, the group for under-25s recently started at Freedom From Torture. What we’d love is to spread our work both within the organisation – Freedom From Torture has centres in Newcastle, Manchester and Glasgow whose clients currently don’t have access to the project), and by sharing our practice more widely with others in the refugee writing community (all ideas welcomed!).

Featured photo: Nalougo, Tracy and Shahab from Write to Life perform at Kings Place with Kuljit Bhamra MBE of NWLive Arts. Photo credit: Hugh Schulte