“I know, I can see, I can tell, I get it”

As an artist who has been through the ringer of NHS mental health systems, has tried to find my own way without it, has made attempts to use art as a form of collective or mutual care, and is currently trying to figure out how these approaches can be layered and blended…, I always come back to a few key moments. Moments that matter to me, and what is common about them is knowing that the person I was engaging with had knowledge that was lived.

It’s 2009. I’m sectioned in the City and Hackney Centre for Mental Health and I’m trying to explain to the staff that I don’t feel safe, but I don’t want drugging. (Seems perfectly sensible in my mind.) But it isn’t going well. I see the staff members’ eyes wandering towards the pharmacy room.

Then something happens. A person, maybe 30 years older than me, comes over. He says, “you’ve had enough, haven’t you?”. And I say, “pretty much, yes”. “I know, I can see, I can tell, I get it”. And I look him in the eyes and I’m like, dude isn’t lying. He gets it. He makes me a tea and talks to me about how he copes, how he manages his struggles. It’s like being injected with hope, instead of haloperidol. I am seen and heard. We see and hear each other.

It’s like being injected with hope, instead of haloperidol. I am seen and heard.

It’s 2019 and I’m working in the children’s mental health ward at Great Ormond Street Hospital making a piece for the Being Human show at the Wellcome Collection. At lunch time I get that all too recognisable feeling of the beginning of a panic attack. I’d say a 7 on 10 one. 10 being a trip to A&E and 1 being a ‘whatever body, you’re not interrupting my day’. A 7 on 10 would require medication, which means the rest of the day is a write-off. But the children are still expecting the session to continue that afternoon.

With my collaborator, the excellent Caroline Moore, we decide that rather than phoning in to cancel the afternoon, it would be cool to model what we believe. So, I go to the ward, a little sedated, and explain: “I’ve had a panic attack and I’m going home, I will be back tomorrow. I just need to look after myself.” And the young people, they say… “I’m sorry you aren’t feeling good James, but I’m glad you told us”. “Yes, that’s different,” another one pipes up.

With my collaborator, the excellent Caroline Moore, we decide that rather than phoning in to cancel the afternoon, it would be cool to model what we believe. So, I go to the ward, a little sedated, and explain: “I’ve had a panic attack and I’m going home, I will be back tomorrow. I just need to look after myself.” And the young people, they say… “I’m sorry you aren’t feeling good James, but I’m glad you told us”. “Yes, that’s different,” another one pipes up.

“I know, I can see, I can tell, I get it”. “That’s different”. It’s powerful to relate to one another, to have what can be frightening experiences validated, understood, even believed. So, my question is… Do we see that in the leaders of NHS mental health trusts, charities and even mental health arts organisations? Are we relating to one another’s experiences?

In some cases, yes, and definitely more so in the arts and definitely more so in smaller organisations. Are we a movement of people struggling with our mental health and have leadership across the board? No.

That isn’t to say that our allies and co-workers are the enemy, bad people, without empathy. Because I have met wonderful mental health professionals, cultural workers and so on. Meeting me where I am with tenderness, openness and with a deep respect for the knowledge that living for 25 years with mental health struggles has given me.

But, and I do think it is an important but: those with lived experience are not leading. Debates continue to happen about mental health: if it should be treated? How it can be treated? How the treatment can be a treat? And so it leads the question of why, why aren’t we leading? And, what would happen if we did?

Sometimes, and again not always, I get the feeling people confuse struggling with weakness, with a lack of knowledge. That in a world of delivery focused production, there isn’t space for struggling. If you are ‘mad’, you are not able to lead, because you can’t be consistent – some days you may want to hide, or cuddle your dog, or you may scream in rage and be ‘totally unprofessional’. (I think sometimes raging is the most professional response I can imagine –provided you are happy to be accountable for it and do the work.)

I wonder also about what it means to admit that we don’t know, or that we are in the wrong process, and we may have to radically change direction. What if the past 10, 50, 100, 1000 years of mental health knowledge has got lots wrong? What would happen if lived forms of knowledge were centred? (And by centred I mean with accountable power, I don’t mean with some weird ‘service user group’, so your opinions can be considered. “Considered”… lol).

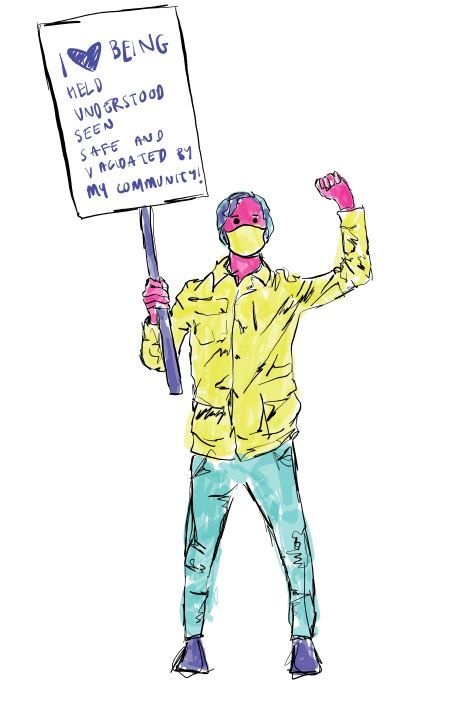

If mental health services were led by people with lived experience, how much more tender, kind, soft, human-focused and non target-driven would they be? What if the arts, led by artists and arts professionals who have been through the wringer, was about making space for others who are having a wobble with their mind/bodies? Raising ourselves and our communities up.

I can’t prove this idea through data, in a clean little graph about how a mental health world led by those with lived experience would be better. Because I don’t need to, in the same way that other marginalised groups shouldn’t have to either. What if the disability mantra of ‘nothing about us, without us, is for us’ became the embedded mantra of arts organisations working in mental health? I get the feeling the work and how it affected us would be better.

What if the disability mantra of ‘nothing about us, without us, is for us’ became the embedded mantra of arts organisations working in mental health?

What I know, and what we all know, is that shared experience matters. And when systems of power and privilege are involved, it matters even more. I’ve learnt from the 1,000s of people I’ve had the huge privilege of meeting through my artistic practice that when I take a risk and share my experience, others can take the same risk and share. And ultimately, we begin to trust each other. From there we can make powerful art, because we feel safe to do so. We begin to transform ourselves, each other and what it means to be in a problematic system, by saying, as that older man on the ward in Hackney said to me “I know, I can see, I can tell, I get it”.

About the author

the vacuum cleaner is the name of a UK based artist and activist who makes candid, provocative and playful work. Drawing on his own experience of mental health disability, he works with groups including young people, health professionals and vulnerable adults to challenge how mental health is understood, treated and experienced.

He is currently working on a project called the Barmy Army, a part art, part activism and part mutual care project led with young people in Manchester and Liverpool with the aim of improving young people’s mental health care. This is supported by the Baring Foundation.

And he’s also working on a new London campaign called 2.8 Million Minds working with young people on a new strategy for the GLA on improving young Londoners mental health through art and culture.

Profile photo: Stephen King 2019