I have spent the last week in North Rhine Westphalia (NRW) as the happy guest of Kubia – the Centre of Competence for Creative Ageing and Inclusive Arts, a training and coordination centre dedicated to raising the cultural engagement of older people in the region.

We are keen to get a picture of and share how other countries approach this opportunity – and Germany was the next step in a journey that has so far involved Japan and the Netherlands.

A week is never long enough and NRW is only one, if relatively large (population around 18 million), corner of Germany. But NRW was an early adopter and innovator in creative ageing – and therefore a good place to start, with a lot happening on the ground and leadership from Kubia and support from the regional government.

Jobbing artists in the UK may be surprised to learn that Germany has a social insurance scheme for artists, paid into by the state and by cultural organisations that hire them, which is intended to provide for sick pay, pensions and so on. Politicians have tried to take a knife to it over the years, but it continues and does reflect a level of regard for the social contribution artists make.

To me, this regard is reflected in the ambition to develop participatory arts and culture for older people into a profession, with recognised career pathways. The Germans call this emerging profession ‘Kulturgeragogik’. A rough translation might be something like cultural gerontology. Emerging from the feeling that pedagogy – linguistically and in practice inextricably linked with children’s learning – was not appropriate to describe work with older people, the idea is that it reflects the needs, interests and capabilities of older people. Since 2008, many people – from the cultural field and care professions – have now taken long and short courses in Kulturgeragogik with Kubia and the University of Applied Sciences in Münster. The belief is not that we cannot all be artists without artistic training. Rather it is that training and the building of an academic discipline are an essential part of making art for and by older people a right not a privilege, and of ensuring that it and its practitioners are taken seriously and continue to be supported.

It is not all about professional development however. A survey by Kubia counted about 80 theatre and dance groups involving older people across NRW. All different shapes and sizes from participatory theatre to professional groups performing classic and contemporary theatre pieces. Museums and galleries across the state are developing their offerings for older visitors, including people with dementia. Like the UK, the generational divide is a cause for concern in Germany, but intergenerational and community arts involving old and young seem particularly vibrant. To mention just a few:

For the active older person:

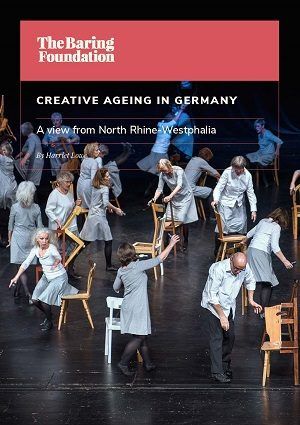

- Altentheater Köln. Tucked away in the cultural southern district of Cologne, the Altentheater is perhaps a world pioneer as much as a German one, having been started almost 40 years ago by the wonderful Ingrid Berzau and Dieter Scholz. The actors range from their mid-sixties to mid-nineties and pieces are co-created with them. The piece I was lucky enough to see was created out of their childhood memories. Many of the current older generation were born in the 1920s, 30s and 40s and their memories are marked by the war – lost parents, lost homes, lost childhoods. All of which made for powerful theatre. The show was punctuated by folk songs (Lieder), some in the local dialect of Kölsch.

For people living with dementia

- Dementia + Art, Cologne and beyond. Dementia + Art is a small organisation set up by Jochen Schmauck-Langer who leads tours in several of Cologne’s excellent museums and galleries. Having dementia can be a constant and wearing discovery of things you can no longer do. Jochen’s tours are therefore deliberately not about communicating art history but focus on feelings and the senses – on what people can still do and contribute. He also includes music and singing (sometimes Volkslieder, sometimes from the early days of pop) in his tours and often ends with what he describes as the best picture in Cologne – a view of the famous cathedral with its twin spires. The cathedral emerged from the war virtually unscathed and became a symbol of the city’s survival, and still exerts a powerful emotional pull for many older people. Interestingly, many of the open tours that Jochen does are attended by people without dementia as well, who seem to find the accessible format of the tour equally appealing.

For old and young:

- Keywork, Düsseldorf. Keywork has its own philosophy which draws on the theories of Josef Beuys, a famous German artist and theorist who believed the practice of art could transform us and our social relations. Amongst other things, it runs intergenerational art projects with an emphasis on art in everyday places in everyday lives. One project has set up creative workshops in local primary schools. Children come to the workshop (between the end of formal lessons and their parents picking them up) as and when they wish – as long as they come with an idea of what they want to make. Older members of the community (often men, as woodworking is a major component) come in to help out.

Overall, my impression of the work going on in NRW was of a passion for quality, for culture as a right not an instrument, and a strong desire to improve inclusion, whether between generations, of older people with dementia, or older people with little history of cultural engagement.

A slightly longer report will follow, but in the meantime, I’ll quote Otto (Actor, Altentheater Köln) who at the end of the curtain call said: ‘so nice that you came’. I felt the same.