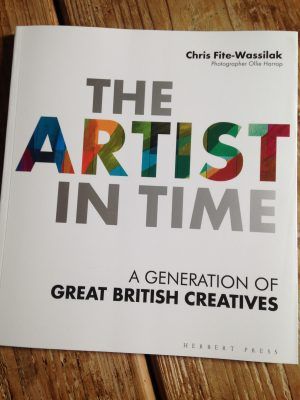

This interview is published in The Artist in Time: A Generation of Great British Creatives by Chris Fite-Wassilak, with photographs by Ollie Harrop. More details about the book below. You can hear Bisakha talk about her work at a virtual launch for the book on 28 October 4.30-5.30pm – tickets available here.

Bisakha is a dancer, choreographer, and facilitator. Trained in classical and creative Indian dance, she has performed and led countless workshops and conferences across the UK. She is the founder of the Chaturangan Dance Company.

Along time back, in an artist’s workshop, somebody said, ‘Tell us one thing that drives you to do this sort of work.’ I remember I said: family. Having left a family of friends and a community back in India, I had an urge to create a new family and friends here in the UK. And that’s why, perhaps, I have taken the route that I have.

In India, I had studied statistics; I also trained in dance, but it was something I did for enjoyment. I came to England as an adult, with an idea of working as a statistician. I found it was quite a different England from what I had imagined, I thought it would be a lot less traditional. Then I had a child, and that changed my lifestyle, having to do all kinds of housework and managing everything. Since then, my dancing career has always run in parallel with domesticity. I didn’t drive in those days, and I didn’t really know many people, so I used to bring my little girl in to the city centre. One day, I walked through an archway to a garden, and I immediately fell in love with it. I thought it was my hidden garden. Then I looked around, it was the Bluecoat arts centre, so I found the offices and introduced myself, telling them that I dance and if they have any events to let me know. Around the same time, I found out about a garden party that was happening in connection with the English-Speaking Union, so I contacted the organisers and asked them to give me an opportunity to dance. They agreed – that was the first time I danced in Liverpool. Through things like that, I got to know a few people, and one thing led on to another.

I didn’t really know any other Indian dancers in Liverpool around that time, in the early seventies. I would do things for the Indian community, in temples or community halls, and then I began to offer workshops and later I was invited to be part of the Bluecoat’s advisory panel for dance, I believe I was their first non-white panel member. That’s where I got to know about the dance field around the city and the north west, and to get opportunities to take part in dance events and performances.

Each of us have to embrace new forms of tradition. We make tomorrows, and tomorrow they will become past.

In this country, if I wanted to dance I could not restrict myself to just dancing on professional stages. I went to all sorts of different places: community centres, day centres, old people’s homes. It was a huge challenge to work with communities who might have never even seen Indian dance. People have said that the work that I have done has bridged the gap between cultures. I don’t like the word ‘bridge’, which always means there is a separation. I try to delve to the riverbed, if you like, to find things which are of common interest. That was a big shift for me in my thoughts on dancing, focusing not on the technical skill of my traditional training, but on finding ways to really communicate with people, to feel that we are all going through a single journey.

If something is alive, then it changes. You need to be rooted, but to grow you also need your branches, which breathe the air of the moment, and take in the sunshine of the place where you stand. You have to have a balance between what’s traditional and how far you are prepared to move with time. The places you perform, people you perform with, your own understanding, the way you look at the world, your connections are all relevant; I allow all of those to influence me. Tradition is being made all the time. You don’t have to be too precious and think of tradition as something that cannot change. Each of us have to embrace new forms of tradition. We make tomorrows, and tomorrow they will become past. In my life I’ve met so many wonderful people of all ages just by doing this work. I found a kind of new person in me, and it is all of those encounters that have made me who I am today.

Most of my dancing, in those days, was through teaching. I started working with young children, doing projects in schools, learning how to find the language to connect with them. I would do the movements, and they would find their own ways to describe them: like the washing machine, the wipers on the car. It was a way of giving them some of the power, to imagine and make their own connections in their minds. Around that time, I was working for an insurance company and I was asked by a colleague to dance at a fundraiser for guide dogs. That was a turning point in my life. I thought, I’ll be dancing to help people with visual impairment, but I’ll be doing something that may not be accessible to people with visual impairment. It really bothered me. How can I exclude the very people that I’m meant to be helping? I really had no training in this field, I didn’t know what to do. This led me towards my work with dance and disability, involving people with a range of physical disabilities and learning difficulties. I started by thinking about extra-visual and integrated dance. What dance is, really, is an engagement with energy. You can put your arm in a straight line or a curved shape, and allow the energy to flow along that. As you move, your relationship with gravity keeps changing. So for me, dance is a play of energy. For visually impaired people, I tried to create movement motifs that could work like building blocks, things I could teach to help them to imagine a dance. Using music and the emotions that it gives internally, people can create their own imaginary dances and join as I dance with them.

Throughout my life I’ve tried to keep my performing career going parallel to my role as a community dance facilitator; I don’t see a separation between the two. In the early eighties, I worked for Merseyside Arts as their first Asian dance ‘animateur’ outside London, to make Indian dance accessible to a wider community. This gave me the chance to use dance in a creative way in all kinds of situations, both in education and in the community. At the same time I met a fellow dancer, Sanjeevini Dutta and formed Sanchari Dance company. We produced and toured many new style performances all over the country, as well as making teaching resources. Eventually, I set up my own dance company, Chaturangan, creating new dance productions, supporting artists to make new work and organising conferences on topical issues.

Throughout my life I’ve tried to keep my performing career going parallel to my role as a community dance facilitator; I don’t see a separation between the two.

I don’t practise every day, not really. But I do dance every day: every morning I like to settle myself, doing a dance as a prayer. Otherwise I just dance whenever there is an opportunity to dance. My dance pieces don’t start with any fixed, clear idea. Some choreographers see the image right from the beginning. I’ll get an idea and I’ll desperately want to do something with it – I can sense it taking shape, but what it is, I don’t know. Just believe that it will come. I think you have to have an open mind, and not have one fixed idea. I have to remain sincere in my attempt to do what I do.

I’ll get an idea that inspires me, it could be from a photograph, or an email. I want to communicate it, I want to say it straight out. That’s the starting point. Then I’ll bring other people together to discuss things, and share our lives’ experiences. Recently I had knee replacements, and I wasn’t moving much. But the brain needed to dance even if the body could not do much. I went along to a gallery just to do something in the afternoon, where they were announcing the name of an artist working with the CERN lab in Switzerland. It really shook me to learn about the lab and the hidden quantum world, I came out of the gallery all excited. I wanted to create something, to share a layman’s excitement about that world. I don’t want to talk about science, because any scientist can talk about that better than me. But dancers speak in their own way, with their own kind of intelligence. I can show an artist’s excitement for an idea, an artist’s translation of an idea. So a few of us who often work as a team – a visual artist, a musician, a poet, an illustrator and a dancer – put something together, and presented it at the planetarium. I trust a group of people that I’ve been working with to pull their own thoughts together, to bring new ideas and think for themselves. That’s how a work grows. It’s a gesture of sharing, to create a bigger picture. All those things create layer upon layer, and the more layers you have the richer the work gets. Every movement becomes more meaningful. There are huge chunks of moments of uncertainty, when you think it will not come together. It just needs everybody’s trust, you know?

Dancers speak in their own way, with their own kind of intelligence.

You cannot respond to every issue that catches your attention. But I think every artist has got a responsibility. Your purpose of life in every way is to respond to the world around you. As an artist, you just do that in a slightly different way, by communicating your feelings, often reaching out to unknown people. That desire to reach out, to connect, to share your own feelings, is what I try to do, and that’s what keeps me going.

The Artist in Time is available from the publisher, Bloomsbury/Herbert Press, and from all good bookshops. If you’re a grantholder of the Baring Foundation’s Arts and Older People programme, we will be sending out copies when we are able to later this year. If you are attending our virtual launch for the book on 28 October (tickets available here), Bloomsbury are also offering a 25% discount.

The Artist in Time is available from the publisher, Bloomsbury/Herbert Press, and from all good bookshops. If you’re a grantholder of the Baring Foundation’s Arts and Older People programme, we will be sending out copies when we are able to later this year. If you are attending our virtual launch for the book on 28 October (tickets available here), Bloomsbury are also offering a 25% discount.