David Cutler reflects on how galleries, museums and arts organisations are widening opportunities for more of us to carry on participating in the visual arts into later age.

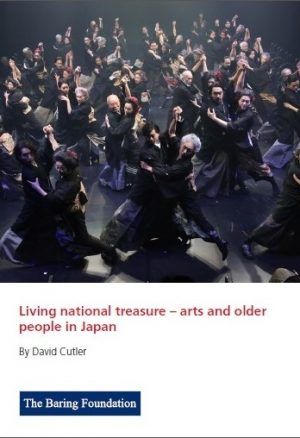

The current exhibition at the British Museum of the sublime Hokusai, probably one of the most famous artists of all time for his Great Wave painting, reminds us that he should be the poster boy for creative ageing. He used dozens of names through his life including Gakyo-rojin Manji – ‘Old Man Crazy to Paint’. At the age of 61 he had renamed himself ‘One Again’ to signal he was starting over. He had strong views about age, saying that nothing that he drew before the age of 70 was worth keeping. He thought he ought to be very good by 100 and ‘at the age of 110 years old every stroke will be as though alive’. He died in 1849 in his ninetieth year, of course painting to the end. Japan has an immensely rich approach to creative ageing which we have tried to sketch in our publication Living national treasure – arts and older people in Japan.

There are many transcendent visual artists in older age. Thankfully the Turner Prize has lifted its age restriction and this year includes a stripling of 62, Lubaina Himid. The British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year is by sculptor Phyllida Barlow, aged 73. Tate Britain has just closed a record-breaking show by David Hockney, now in his eighth decade and constantly experimenting as he has done throughout his life. Wayne Thiebaud is being exhibited at the age of 96 in the White Cube gallery. The list could grow almost endlessly from Titian to Goya to the recently departed Hodgkin and Freud. We could probably all choose a favourite and I would vote for American minimalist, Agnes Martin, exhibited last year at Tate Modern.

Many galleries have embraced the dedication to visual arts of older people, whether in terms of appreciation or creativity themselves. The Baring Foundation continues to fund the Age Friendly Museums Network to this end, itself hosted by the British Museum. A lot of consideration has been given by galleries to the needs of people living with dementia, often inspired by the Meet Me at MoMA programme in New York. A major research study to examine whether art can improve the lives of people with dementia and their carers is called Dementia and Imagination. (You may not be surprised to hear the answer is yes.)

The Baring Foundation has funded some inspiring older visual artists through commissions made in our Late Style Programme. These have included Fife artist, Elizabeth Ogilvie, who is currently working on a film installation for Forth Valley Royal Hospital in Scotland, the recently deceased Eric Geddes on the Isle of Wight, and Ron Haselden at Fabrica in Brighton.

Many older people will not get to see great works of art in museums or galleries – perhaps because they are one of the 416,000 who now live in a care home or because they find it hard to get out. Much of our arts and older people programme supports the bringing of brilliant art to them. cARTrefu in Wales brings professional artists into care homes. Armchair galleries are opening up world class art collections to those who cannot visit them themselves.

It is also infused with opportunities for people who may not believe they will become as renowned as Hokusai but share his passion for getting better as they get older. A new grants programme – Celebrating Age with the Arts Council England – for example, is supporting many local organisations across the UK to enable older people to learn and develop new skills and take pleasure in the visual arts.

Who knows, perhaps there are more Hokusais out there than we know.

David is Director of the Baring Foundation.